COVID-19 is affecting every country in the world. But the poorest countries with the weakest health systems are likely to be hardest hit. Mali has one ventilator for every million people. And the kinds of social distancing and hand washing guidance given in Europe and North America simply won’t work for those without access to water and who need to earn an income every day to survive.

Countries are also feeling the economic pinch. Oil revenues are down, tourism has dried up, and costs for food are on the way up. It is estimated that Africa could lose between US$37-79 billion in economic output in 2020, and lead to the first recession in Africa in 25 years. At the same time food prices are likely to increase, as agricultural production in Africa declines and other major food exporters are implementing protectionist measures. This will be hugely detrimental for the most vulnerable populations, already struggling to make ends meet. In fact, the decrease in incomes from COVID-19 fallout could result in up to 420 million more people globally being pushed below the extreme poverty line of US$1.90 a day, erasing decades of progress.

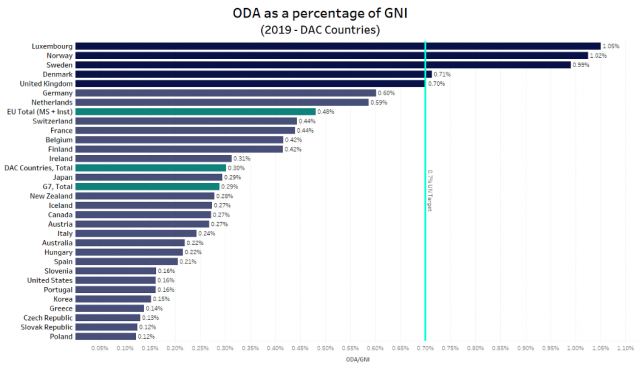

But there is a third wave of harm this virus is going to exact on countries dependent on aid. The latest data on aid released this week show that in 2019, aid levels increased just slightly (up 1.4% in real terms), following the previous two years of decline. While this is on the surface good news, on the whole, aid levels are plateauing. Aid as a share of countries’ national income (GNI) is only 0.30%, down from a high of 0.32% in 2016.

The bad news is that the political will to increase aid as a share of income is limited at best. With a shrinking global economy, this means even the same slice of a smaller pie means less money for the countries hit hardest by the crisis. If advanced economies see a 6% decrease in GDP from 2019 levels, as predictions show, then a corresponding decrease to global aid levels would mean $9 billion less for the poorest.

Low- and middle-income countries will require international aid now more than ever, and urgently, to shore up an emergency health response and provide social safety nets for their populations.

So what needs to happen?

First: immediate debt relief is the fastest way to provide governments with the cash they need, and the G20’s decision this week to suspend debt payments for the poorest countries this year will be a huge boost. But this is only a start covering a third of this year’s debt payments. Private and multilateral lenders should follow suit, extending the moratorium to 2021 and kick starting a conversation about cancellation of debt. Before this week is out, the IMF and World Bank should agree a package for relief of debts owed to them.

Second: extraordinary times require extraordinary measures. The IMF should start printing money in the form of Special Drawing Rights; 500 billion of them. So far the US has been opposed on the basis that most shares would go to richer countries, but they could collectively agree to transfer those shares to the poorest countries to use in their COVID-19 response.

Finally, donors should use this crisis as a wake up call. In a world of pandemics none of us are safe until all of us are safe. Aid must be scaled up to build the global health security infrastructure that is critical to protect everyone everywhere. And resources are needed to safeguard the poorest who will be the hardest hit. If all donors hit the 0.7% they promised to deliver 50 years ago, this would yield an additional $200 billion for investment in health systems and development.

More immediately, the next big moment for donors to step up is on 4 May at the virtual pledging conference to fund a COVID-19 vaccine and make sure everyone has access to it.

We have learnt, to our peril, that international cooperation isn’t charity. It’s a smart strategy to keep everyone safe, whether they live across the street or across the ocean.