This is the second post in a series about how we ensure children are learning in school. We kicked off with an overview of the evidence pointing to a global learning crisis and how we can solve it. Now, we’re looking into global progress in access to education, and where there is still room for improvement.

Improving education is critical to our mission of ending poverty: if everyone completed secondary education, we could cut the number of people living in poverty worldwide in half. To ensure we have the greatest impact, we’re digging deeper into the progress and challenges of access to education.

There are three key things to know about access to education:

First, we have made great progress in increasing access to education. There is still work to do, but we can say, universally, there are more children in school now than ever before and staying in school for longer.

Second, where challenges do exist, poverty is the biggest barrier to educational inequities. This is true both when looking at the poorest children and the poorest countries in the world.

Third, barriers to accessing education are extremely context-specific. As a result, the solutions to poor access to education should be adapted to each local situation.

The world has made great progress in ensuring kids are in school

Today, more children are in school at all levels of education than ever before and children are staying in school longer. This is also true for low-income countries and in sub-Saharan Africa. The years of schooling for an average adult in a developing country have more than tripled, and since 2000, despite an increase in the population of school-aged children by 50%, the global number of out-of-school children has dropped by 30%. These improvements in access to education have been even more rapid for girls.

These significant accomplishments are thanks to the coordinated effort of the global education community, who set improving access to education as a key goal to be achieved by 2015.

But a quarter of a billion children are still out of school

258 million children are out of school, with equal numbers of boys and girls. And when children are in school, they often do not stay there: only 1 in 4 children complete a full 12-year cycle of education in sub-Saharan Africa.

Population growth will pose an additional challenge to improving access to education: Africa’s population alone is set to double to 2.5 billion by 2050, more than half of whom will be below the age of 25. This will require governments to increase investments in access to education to ensure that no child is left behind.

Poverty is the greatest determinant of inequitable access to education

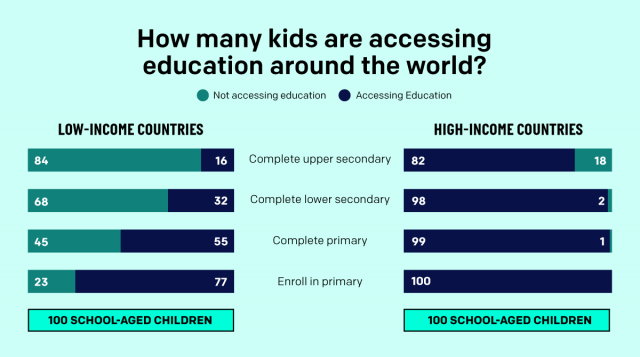

Where are educational inequities the greatest? The answer is entirely to do with poverty: the poorest children in countries and the poorest countries in the world have the worst educational outcomes. Within countries, children from wealthy families are significantly more likely to finish school than children whose families are in poverty.

And when looking across countries, only 16% of children in low-income countries complete secondary school compared to 82% in high-income countries. In low-income countries, 23% of children never enter the education system. That’s more than the proportion of children in high-income countries who don’t complete secondary education.

So what about those who experience both these elements of poverty? The poorest children in low-income countries are hit with a double-whammy: only 4% of them go through a full, 12-year education cycle, compared to 90% of the wealthiest in high-income countries.

Access to education is a hyper-local challenge

While we can say universally that poverty is the biggest barrier to educational access, what this looks like from one country to another varies greatly. For instance, in South Sudan, just 25% of children complete primary school, compared to nearly 90% in Zimbabwe.

What about how gender affects out-of-school rates? Even here, the picture is mixed. While countries like Chad and Niger have more girls who are out of school, other countries like Lesotho, Zambia and Kenya actually have more boys out of school.

And while being poorer means you are always disadvantaged, the gaps in educational attainment between the poorest and richest people in a country vary substantially. For instance, in Somalia, a child from the wealthiest households is nearly 22 times as likely to complete primary school compared to a child living in poverty; in Kenya, this figure is 1.5 times.

So we must ensure that access to education is talked about in a context-specific way.

Here at ONE, we’re committed to ensuring that our campaigning work is grounded in evidence. And we are committed to building on the gains of the past decade by continuing to work on access to education in a context-specific manner where it remains a challenge.

But we must keep in mind that access to education isn’t enough — the ultimate goal should be ensuring kids are learning in school.

Stay tuned for more stories that dive deeper into the evidence and our solutions for better global education outcomes.