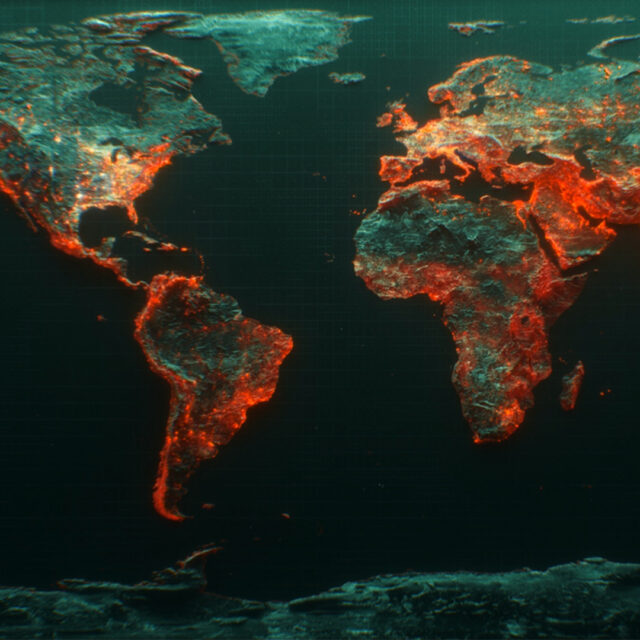

Every day, almost 20 million people in South Africa go to bed hungry. And every month, 30 million people don’t have enough money, leaving them vulnerable to food insecurity.

In Cape Town, community gardens and nonprofits are fighting this food insecurity by rescuing food waste, encouraging people to grow their own gardens at home, and fostering the next generation of agricultural entrepreneurs.

On this World Food Day, here‘s a closer look at their work.

Bo-Kaap Helpers Garden: Building garden communities during COVID-19

Between the brightly painted homes of Bo-Kaap, Abieda Charles and Mishkah Bassadien are teaching the next generation of agricultural entrepreneurs how to plan better for the future at the Bo-Kaap Helpers Garden, formerly the Bo-Kaap Community Garden. Recognizable by her bright smile, Abieda, the project manager at Bo-Kaap Helpers Garden, wraps her hands around the leaves of a spinach plant and tugs it out of the ground.

Since June 2020, 200 families‘ homes in Bo-Kaap have started their own home gardens with starter packages from the Bo-Kaap Helpers Garden. “Many people lost their jobs and with lockdown and [with school closures], there were more mouths to feed during the day,” Abieda said. The community garden equipped people in the community with the tools to feed themselves.

Thanks to the Department of Agriculture, everyone started with the resources and instructions necessary to grow their own garden at home. And through WhatsApp, community garden members can share information safely and trade recipes to help take their home-grown vegetables from farm to fork.

“We are surviving, and our garden is going to be the greatest survivor of all,” Jasmina Issacs, a recipient of one of these starter kits, shared.

“Many started gardens on their balconies, on their back porches, and some even on their kitchen windowsills,” Abieda said. “Our community is so much more aware of wholesome food sustainability since they are growing their own food now.”

“At the end of the day, we need to do more of these community gardens,” Mariam Matthews, another community member benefitting from the garden, added. “COVID-19 has shown us we need to pull together as a community.”

SA Harvest: Rescuing food waste and feeding a nation

In South Africa alone, over 10 million tons of food go to waste every year. That‘s enough food to feed the 20 million people going to bed hungry in South Africa with three nutritious meals every day for over a year. SA Harvest exists to tackle that gap.

Its mission is to end hunger in South Africa by rescuing food waste and delivering it to those in need instead. Ali Conn, “chief harvester” at SA Harvest, says that in South Africa, 39% of the country is food insecure. And much of South Africa‘s food waste comes from farmers not being able to sell their produce to retailers because the food may not be visually appealing or because goods may have passed sell-by dates.

“A small-scale farmer in Philippi gave us a call a couple of days ago and said, ’We‘ve got 4 tons of carrots that we can‘t move because [the retailer] doesn‘t want them. They‘re too small,‘” she shared. “We [also] collected 40 tons of oranges a couple of months back … because the retailers didn‘t want it,” Ali added.

By partnering with retailers and farmers, SA Harvest redirects what is nutritious, soon-to-be wasted food to soup kitchens in Nyanga and Lavender Hill, and to nonprofits dedicated to improving people‘s lives, like Mercy Aids.

Since their start in October 2019, they‘ve rescued over 3 million kgs of potentially wasted food and delivered over 10.5 million meals across South Africa. Many of their meals have gone to children across the country.

Abalimi Bezekhaya: Helping urban farmers grow their business

In the Western Cape, the province home to Cape Town, more than 90% of people buy their food from supermarkets, with very few people growing their own food. That means if someone experiences a loss of income — as many did during the pandemic — they also lose their source of food. Abalimi Bezekhaya is fighting to change that by encouraging individuals to grow their own safety nets, literally.

Abalimi Bezekhaya started in 1982 to promote food gardens and green space in the Cape Flats by planting trees. Beyond starting a green revolution, they‘re also fostering a future for urban farmers in the area. For 70 Rand, less than US$5, they provide farmers across Khayelitsha, Nyanga, and Langa with urban agriculture training, market access, assistance to become certified organic producers, and seeds, seedlings, and compost to get them started.

“Each farmer is an entrepreneur,” said Babalwa Mpayipeli, a field worker and facilitator. Abalimi Bezekhaya is there to help them take their business further. With 50 to 60 community gardens and 3,000 home gardeners, Abalimi Bezekhaya‘s field workers train and assist micro farmers with resources, mentorship, knowledge, and access to markets. This enables micro farmers in poorer urban areas to build their own healthy living and their income by selling produce.

Abalimi Bezekhaya farmers also sell their produce at a discounted price to those in need to help feed the greater community. “We identify houses that are struggling in the community,” explained Zodwa Daweti, a farmer at Moya We Khaya, one of Abalimi Bezekhaya‘s partners. They help with groceries, food parcels, and leftovers from the harvest.

The farmers also employ youth in the community. “We ask for help from the youth that are not working. We pay them and we also provide some veggies for them to take home,” Xoliswa Magutywa, a farmer and founding member of Moya We Khaya, said.

“We work together. Whatever we do, we are doing together,” Xoliswa added. Moya We Khaya‘s farmers are mainly female, many of them retired from other work.

Soil for Life: Teaching how home-grown food can go from farm to fork

Soil for Life, which spans across several areas of Cape Town, is home to a program that teaches community members how to grow their own organic food and, ultimately, fight food insecurity. It‘s a 12-week program that costs home gardeners 20 Rand (just over US$1) for the training, ongoing mentorship for up to 21 months, and a starter pack with compost, mulch, seeds, and seedlings.

“We teach people in communities how to grow their own healthy food and build healthy soil,” Cindy Busk, CEO at Soil for Life said.

“We teach them how to cook the vegetables [from their own home gardens],” Sandi Lewis, the program coordinator, added. By sharing recipes and information about nutrition, Soil for Life teaches people how their home-grown food can go from farm to fork.

“We‘re working with people with very little space. What can they do with a small space? They can actually feed a family of six,” Cindy explained.

During the height of the pandemic in 2020, Sandi taught home gardeners remotely through Whatsapp. One home gardener was Craig, who transformed his garden from flowers and herbs to profitable, nutritious vegetables. Craig uses the garden to feed his family and he sells excess vegetables in his community. “I‘m able to provide income from my garden,” he said. He also gives vegetables away to a soup kitchen.

Sandi and other facilitators visit home gardeners like Craig every two weeks, ensuring they‘re encouraged and empowered to keep life growing in their gardens.

Soil for Life has helped over 6,000 people across Cape Town with home gardens, and they‘ve provided opportunities for employment. Their Train the Trainer program teaches gardeners how to support other gardeners in their community. Some of their gardeners have started their own small businesses selling seedlings, vegetables, and compost.

“They become like a family when they come on the training,” Sandi explained. “Since the training is taking place in their community, they know each other, they share with each other information, they barter with plants or with veggies. It helps build the community.”

Black City Farm: Bringing Langa‘s farming community together

Between the tin shacks of Langa, founder Tony Elvin and the farmers of Black City Farm are nurturing a legacy while fighting food insecurity. They provide established farmers with resources and assist them with access to markets, input on production, and learning through the UCan Grow app. Black City Farm is building Langa‘s farming community and uniting Langa to fight against food insecurity and unemployment.

“How do we aggregate all the growers [in Langa]? That‘s what Black City Farm is,” Tony said.“We‘re grouping together all the growers … in the community from the community level. It‘s important that there‘s a community brand. The idea is we buy what they‘re growing or create opportunities for them to sell what they‘re growing. We‘re doing that commercial side and the community can concentrate on growing.”

Nombulelo Mahlabelo has been unemployed since 2014, and Ntomboxolo Njungwini lost her job in October 2020 due to COVID-19. Working with Black City Farm has allowed them to continue to provide for their families by growing their own garden. They‘ve planted spinach and cabbages, which have grown vibrantly green under the sun.

Across a high fence, honking taxes, cars, and buses blare past on the busy N2 highway. Nombulelo and Ntomboxolo‘s children mill about, chasing each other, and walking carefully through the garden, stopping to examine spinach leaves. Thanks to the resources provided by Black City Farm, their garden is flourishing. They named their garden Yeyethu Injongo. “It belongs to all of us and we‘re planning to take it forward,” Nombulelo says. Their dream is to expand their garden to benefit the community.

“It‘s a wonderful opportunity for Black City Farm to help us to grow some veggies for ourselves,” Nombulelo said. “As we are empowered, we will be able to empower other community gardens.”

Fighting food insecurity together

The Bo-Kaap Helpers Garden, Abalimi Bezekhaya, Soil for Life, Black City Farm, and SA Harvest prove when people work together and take care of each other, they can grow a lot of goodness together.

“We see the power of togetherness and community when we harvest the goodness we have grown,” Abieda from the Bo-Kaap Helpers Garden said.