In 2020, global health has gone from a fringe issue to the forefront of people’s mind, all thanks to COVID-19. The last time the entire world came close to being as focused on a pandemic threat was over two decades ago, when HIV/AIDS was killing almost 4,000 people every day and new infections doubled year after year.

Since then, the global response to AIDS has become a success story, and AIDS-related deaths have been cut by more than half. Today, 25.4 million people are receiving live-saving AIDS treatment.

The success of the AIDS response is a model for what is possible with strong political will and consistent, long-term funding. But these gains are matched with remaining challenges. While over half of people living with HIV now have access to live-saving medicines, 12.6 million people are living with HIV but still not receiving treatment. In 2019, 690,000 people died from AIDS, and AIDS-related illnesses are still the leading cause of death for women under 50.

As we mark World AIDS Day on 1 December, there are two significant questions: What can the fight against AIDS tell us about how to tackle a global pandemic like COVID-19? And how can we prevent COVID from undermining decades of incredible progress tackling HIV/AIDS?

Lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic

Nearly four decades into the fight against AIDS, many lessons learned can be applied to other infectious disease responses. Here are three that should be heeded in the COVID-19 response.

1. Health inequities must be anticipated, acknowledged, and addressed. New infections of HIV are increasingly concentrated among poorer people and countries, and more vulnerable populations like women, men who have sex with men, and sex workers. Similarly, COVID-19 impacts certain groups more than others, and it’s crucial to understand the nature of the pandemic at the community level and tailor interventions for the most vulnerable. COVID-19 will not affect everyone equally, and a blanket approach to prevention and treatment risks leaving the most vulnerable populations behind.

2. As effective new treatments and vaccines come to market, they must be made available to all vulnerable groups, no matter where they live. The AIDS response tragically demonstrated that when market dynamics drive access to health technologies, it costs lives. When effective AIDS treatments were discovered, it took almost two decades for them to become readily available to the hardest hit populations in Africa, partly because of restrictive pricing and patent laws. We risk a similar outcome with COVID-19, with a small group of wealthy countries having already purchased more than half of the expected supply of leading vaccine candidates. Policymakers must upend this precedent and prioritize access to health innovations for those individuals in greatest need.

3. Political leadership matters. Early in the AIDS pandemic, political leadership was glaringly absent. Many heads of state refused for years to even acknowledge the existence of the deadly virus, helping fuel stigma and thwarting efforts to promote prevention and behavior change. The COVID-19 response has already seen more political leadership. A coalition of international institutions have set up the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), which is positioned to deliver a coordinated global COVID-19 response at scale and speed. But we have also seen where leadership has failed — where politicization of the virus has superseded science, and lives have been unnecessarily lost. World leaders must follow the science and work across borders to advance collective efforts.

COVID-19’s impact on HIV/AIDS

Even before COVID-19, UNAIDS reported that the world would fail to reach any of the 2020 targets set to benchmark progress toward ending the AIDS epidemic.

Now, COVID-19 risks blowing HIV progress further off course. People living with HIV are at greater risk of developing more severe disease if infected with COVID-19. Lockdowns and other social distancing measures are affecting the ability of those with HIV to access vital health services services. As of the end of October, nearly 20% of countries were still experiencing high levels of disruption in services that deliver prevention, testing, and treatment support for people living with HIV.

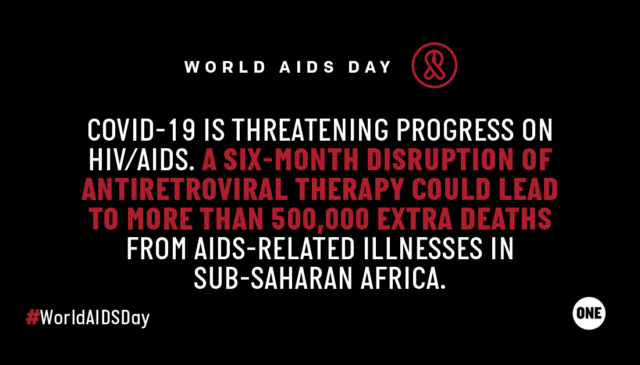

These disruptions have deadly consequences: if health systems collapse or treatment and prevention services are interrupted, the death toll from HIV, TB, malaria, and other diseases could exceed deaths from COVID-19 itself. A six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy due to COVID-19 could lead to more than 500,000 extra deaths from AIDS-related illnesses, including from tuberculosis, in sub-Saharan Africa.

Responding to this moment

Thanks to decades of investment, there are people, programs, and systems with the experience to respond to pandemic threats like HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 alike. Among them are Global Fund, PEPFAR, and UNAIDS, which are working alongside countries and international organizations to stop the spread of COVID-19 and mitigate its impact on HIV services.

To date, the Global Fund has committed $1 billion in existing funds to support countries as they respond to the pandemic, adapt programs and services, and reinforce overstretched health systems. The Global Fund is also lending its expertise to help scale up access to COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics globally.

Similarly, PEPFAR is providing programs flexibility and adapting technical guidance to ensure PEPFAR-supported health services meet the diverse needs of clients during the pandemic.

UNAIDS has developed guidance on how existing health infrastructure focused on HIV/AIDS can also be used to respond to COVID-19, as well as guidance on reducing stigma and discrimination during the pandemic response.

In order to retool the AIDS fight for the next decade, we must invest fully in the colliding epidemics of HIV and COVID-19, focus on the most vulnerable and hardest to reach people, and unlock more sustainable funding for HIV/AIDS and resilient health systems.