Beatrice, a beautician at a spa in Nairobi, first tried to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in June. But all the health facilities she visited turned her away because they had no vaccine doses. All had either not received any supplies or they had run out. Eventually, she received her first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine at a health facility some 50 kilometres outside the city.

When it was time to get her second shot, Beatrice was told she might have to wait a few more weeks, due to a lack of supply across the country. She finally managed to get her second dose after waiting in line for nearly five hours at a major referral hospital in Nairobi some weeks later. Beatrice is eager to get a booster shot, but it’s unclear when the country will have sufficient supply to begin offering them.

People across Africa are facing the same challenges as Beatrice in getting vaccinated. And many are now perplexed and angry over the emerging narrative in global media that vaccine hesitancy is to blame for disturbingly low vaccination rates across the continent.

Since South Africa’s discovery of the Omicron variant, media coverage is increasingly citing vaccine hesitancy as a key reason why Africans are not being vaccinated in large numbers. Yet studies tell a different story. A 2020 Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention study in 15 African countries found that 79% of respondents wanted to be vaccinated against COVID-19. That figure is higher than in some European countries, such as Germany, where nearly one out of every four people (23%) said they did not want to be vaccinated. Vaccine hesitancy was as low as 4% in some African countries. Less than 10% of respondents in countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia, and Tunisia were reluctant to get vaccinated. Only 3 of the 15 countries (Cameroon, Algeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) had vaccine hesitancy rates that surpassed 60%.

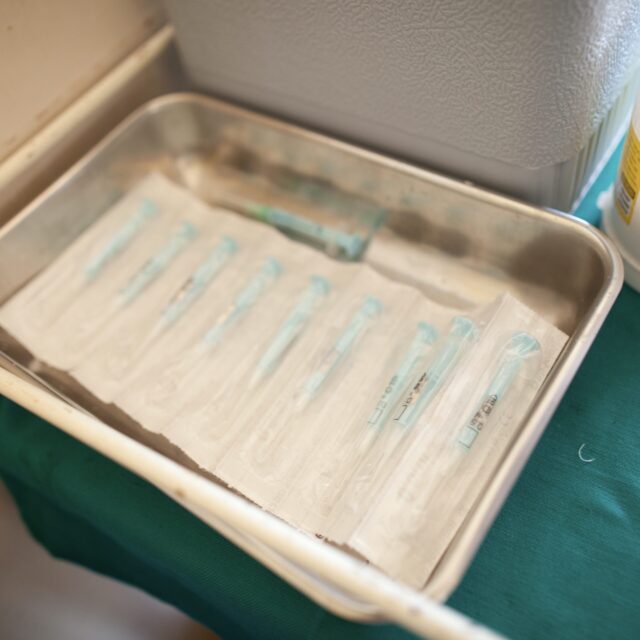

Insufficient supply

Africa, with a population of 1.2 billion, has received 375 million COVID-19 vaccine doses. Half of those came from COVAX, the global vaccine-sharing facility, and 23 million came from the African Union’s COVID-19 Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT). Bilateral arrangements accounted for 160 million doses. Two-thirds of these doses have been administered.

More than 8 billion vaccine doses have been administered globally. But just 253 million (3%) of those doses have been administered in Africa. Less than 2% of the populations in Nigeria, Ethiopia, and the DRC – three of Africa’s most populated countries – have been fully vaccinated. The main reason for these low vaccination rates is not vaccine hesitancy – it’s a dire lack of vaccines and means to administer them.

There has been a lack of global progress to deliver more vaccines to Africa. The Biden administration recently promised to send 9 million additional doses to African countries, for a total of 100 million. The US also pledged to support sub-Saharan African countries with vaccine access and delivery. China’s President Xi Jinping pledged 1 billion doses to Africa. Yet supply and distribution issues continue to hinder vaccine access for most Africans.

Vaccination obstacles in Kenya

Only 10.8% of Kenya’s adult population was fully vaccinated as of early December, according to official data from Kenya’s Ministry of Health. Vaccination rates vary widely across the country. The capital Nairobi has a vaccination rate of about 17%, compared to less than 1% in remote, sparsely populated counties such as Mandera, Marsabit, and Wajir. This poses formidable challenges for the government to get vaccine doses into the arms of the millions of citizens wanting to get vaccinated.

Dr. Abdinasir Amin, a public health specialist who was born in Wajir, says that poor rural road networks and urban-based vaccine distribution centres have further hampered vaccine uptake, especially in largely rural or marginalised regions of the country. He says that people living in semi-arid places like Wajir often have to travel several hundred kilometres to reach the nearest health facility, and few are willing to do so unless absolutely necessary given the time and money involved.

“You are delivering COVID-19 vaccines in the context of a public health system that is highly skewed and unequal. Low vaccination rates in areas that have very few or poorly equipped public health facilities are a reflection of this unequal system. You cannot deliver COVID-19 vaccines across the country when many counties are still struggling to provide basics like maternal healthcare or mosquito nets to people living in malaria-prone areas,” he says.

Dr. Amin believes that in a predominantly rural country like Kenya, mass public information campaigns that let rural or pastoralist communities know where and when to get the vaccines could greatly benefit vaccination efforts. Mobile clinics that can administer the vaccines directly to these communities would also help.

High demand

The demand for vaccines is so high in Kenya that it has led to a black market in vaccines. An investigation by the Sunday Nation revealed that unscrupulous officials and their agents are diverting vaccines from health facilities and selling them to individuals for between $30 and $50 each. This has raised serious safety concerns, as some of the vaccines are being transported without adequate refrigeration. Vaccines that are smuggled out of health facilities could also be contaminated.

Kenya initiated a 10-day mass vaccination campaign on 26 November, with a target is to vaccinate 10 million Kenyans, or about 20% of the country’s population, by the end of this year. The government hopes to vaccinate 26 million people, or about half the population, by the end of 2022. Mutahi Kagwe, the health minister, assured Kenyans that the country is expecting to receive over 1 million doses every month and can therefore meet these targets. However, Kenya’s targets are still low compared to European countries and North America, where vaccination rates have already surpassed the 70% mark.

Yet despite the relatively low vaccination rates and targets, Kagwe issued a directive last month that all unvaccinated Kenyans will be denied government services and banned from public transportation starting on 21 December. Critics say that the directive is unrealistic, as more than 20 million adults in Kenya are yet to receive their first jab — not because they don’t want to be vaccinated, but because there aren’t enough vaccines in the country or because the vaccines are poorly distributed. The ban will negatively impact people who – through no fault of their own – could not get vaccinated by the deadline due to insufficient supplies or lack of access to health facilities.

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist who is working with the ONE Campaign’s COVID-19 Aftershocks project.