Conchita Wurst, winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 2014, during the winner’s press conference. Photo: Albin Olsson. License: CC-BY-SA-3.0

Could it be that a bearded man in a dress has rekindled Europe’s appetite for democracy?

It has emerged that the winner of last weekend’s Eurovision Song Contest, Austrian drag act Conchita Wurst, was not the choice of the elite juries that cast half the votes in the annual Euro-singathon. Instead, Wurst swept to victory thanks to the support of the public, who decided that behind the camp persona and hype there was actually quite a good song (at least, relative to the others). Conchita was the people’s choice.

After this flexing of mass muscle, perhaps European voters will now relish the chance to go to the polls again – for an electoral contest on which lives really do depend. For four days between May 22-25, people across Europe will vote again, this time for the 751 Members* of the European Parliament (MEPs).

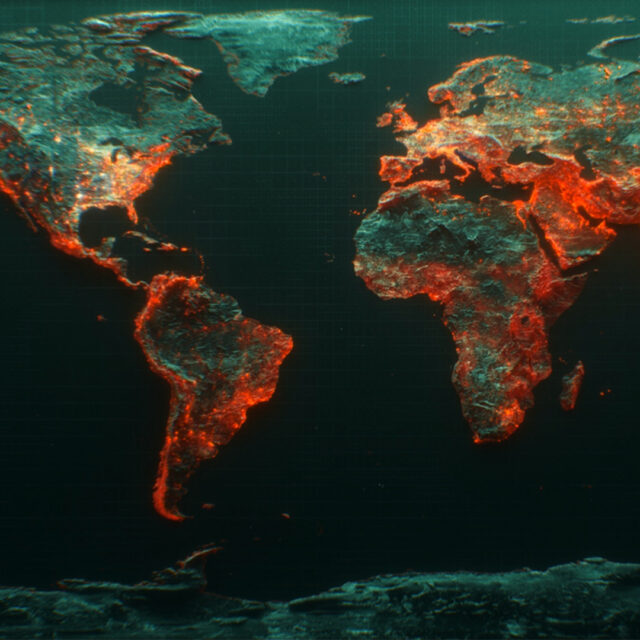

Representing the 28 member states of the EU, these MEPs will decide the path the continent will take over the next five years. Crucially, the issues they will have to consider won’t be limited to matters within Europe, but the continent’s role on the global stage as well. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Europe’s role in the fight against global poverty.

The European Union is the world’s biggest multilateral aid donor, so how it uses this money counts for millions of people outside Europe. It’s easy to see why. Between 2004 and 2012, EU aid has meant more than 70 million people can access safe drinking water for the first time, given 7.7 million people technical and vocational education and training, given 13.7 million children a primary education and vaccinated 18.3 million children against measles.

Advocates in both pro- and anti-EU camps can agree on one thing at least: on aid and development, Europe’s collective clout achieves more than one country can by acting alone. Take Eritrea as an example. This country receives no bilateral aid from the UK, France or Germany – yet is the fifth poorest in the world. However, it does benefit from aid via the EU. Eritreans have better levels of health, education, nutrition and security than they would without this provision. Through Europe, member states gain global influence and the knowledge their support is going beyond their individual reach.

Thanks to the efforts of the EU and its member states, in support of effective leadership in many developing countries, we are at a turning point in this struggle. There is a very real opportunity that extreme poverty –people living on barely £1 a day – can be eliminated in by 2030. But that will require exceptional drive from within Africa in particular, supported by smart finance and policies from European and other partners. It starts with this new European Parliament, and each and every MEP.

If the next political generation to arrive in Brussels steps up its effort to ensure justice for the world’s poorest, there is a real chance that within a decade and a half no one will have to struggle each day on less than the price of a bus ticket. If Europe continues to invest in agriculture (the largest employer in sub-Saharan Africa), maintains financial support for life-saving vaccines (which bring an economic benefit many times the price of one shot) and makes determined efforts to tackle corruption and unscrupulous business through ‘Phantom Firms’ (which have cost developing countries more than $6 trillion since the millennium), then the developing world may actually be able to lift itself out of extreme poverty.

If MEPs are committed to this, then they must sign the ONE vote 2014 pledge.

*750 MEPs and 1 president will sit in the EU parliament this time around – a reduction from last time.

This blog was first published in the Huffington Post Blog.